Aug 24, 2022 The History of Cookbooks

They’re given as gifts, they’re cherished as heirlooms, and yet they’re also covered with grease stains and contain granules of sugar deep between their pages. They are our cookbooks. They help us get dinner on the table, remember cherished traditions and explore new cuisines.

But the newer cookbooks that line our pantry shelves are not like our parents’ cookbooks. We love them just as much, but admittedly they’ve changed: “What once were primarily vehicles for recipes became anything but: the recipes still mattered, but now they existed in service of something more—a mood, a place, a technique, a voice,” writes Helen Rosner, in “The Best Cookbooks of the Century So Far” from the July 14, 2019, issue of The New Yorker.

But exactly how did this transformation happen? How have cookbooks changed throughout history? When was the first one published? What do cookbooks reveal over time about changes in food preparation? What do they have to say about us? To answer these questions, we did a little research, then we scoured our kitchens and the shelves of the Library and found a delectable history that tells a story even bigger than the cookbooks themselves.

During the month of September, check out our display The History of Cookbooks: The Human Story Told through Recipes, Food Preparation, and Cooking Techniques. The display is available to view at the 5th Street entrance of the Library, but you can also explore the history online here. We’ve included links to The Library of Congress and other websites, where you can see digital copies of some of the oldest books that are now in the public domain, and to the HMMPL Library catalog, where you can find the books included in the display and even place them on hold. Simply click on the images below to explore each resource. We hope this post will give you much more information than we could fit in a display case.

Are you ready to learn more about the history of cookbooks? Let’s get started.

1700 BCE – 1750

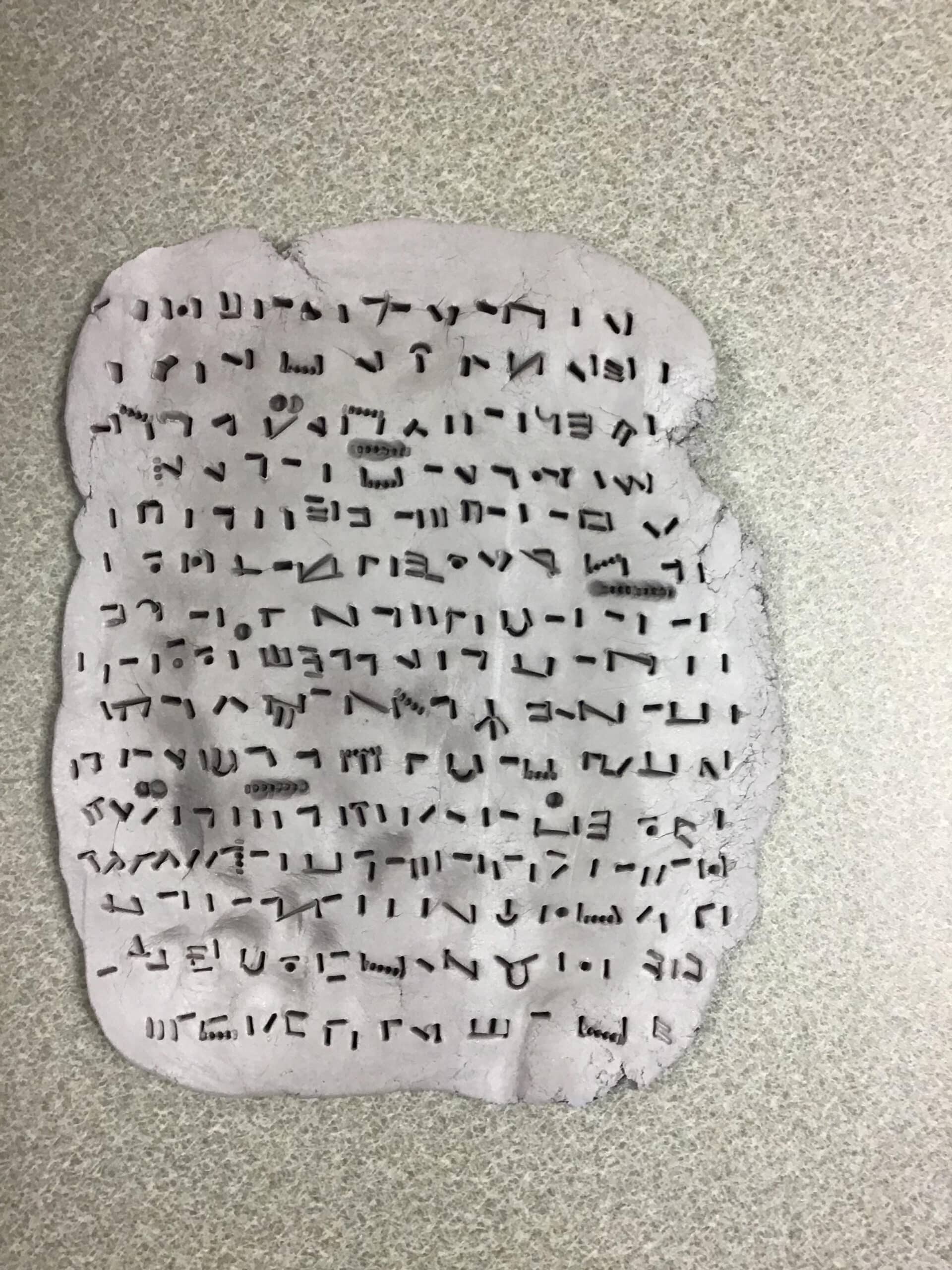

The earliest cookbooks–from those etched into cuneiform tablets in ancient Mesopotamia to the first cookbook in English called The Forme of Cury–included the meals of royalty and were prepared by and for their kitchen staff.

- 1700 BCE – Cuneiform Tablets from Ancient Mesopotamia

- 1390 – The Forme of Cury, A Roll of Ancient English Cookery

1750 – 1890

The first American cookbooks, published by Colonial settlers, demonstrated both a reliance on and shift away from English culture and traditions. They also, along with English cookbooks of that day, reflected a shift toward a working class audience made possible by increased literacy and a proliferation of printed materials during those years.

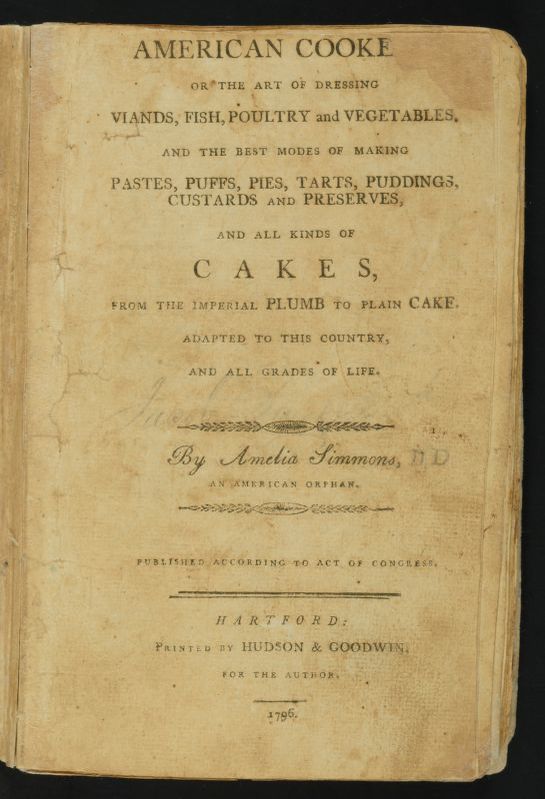

- 1796 – American Cookery by Amelia Simmons

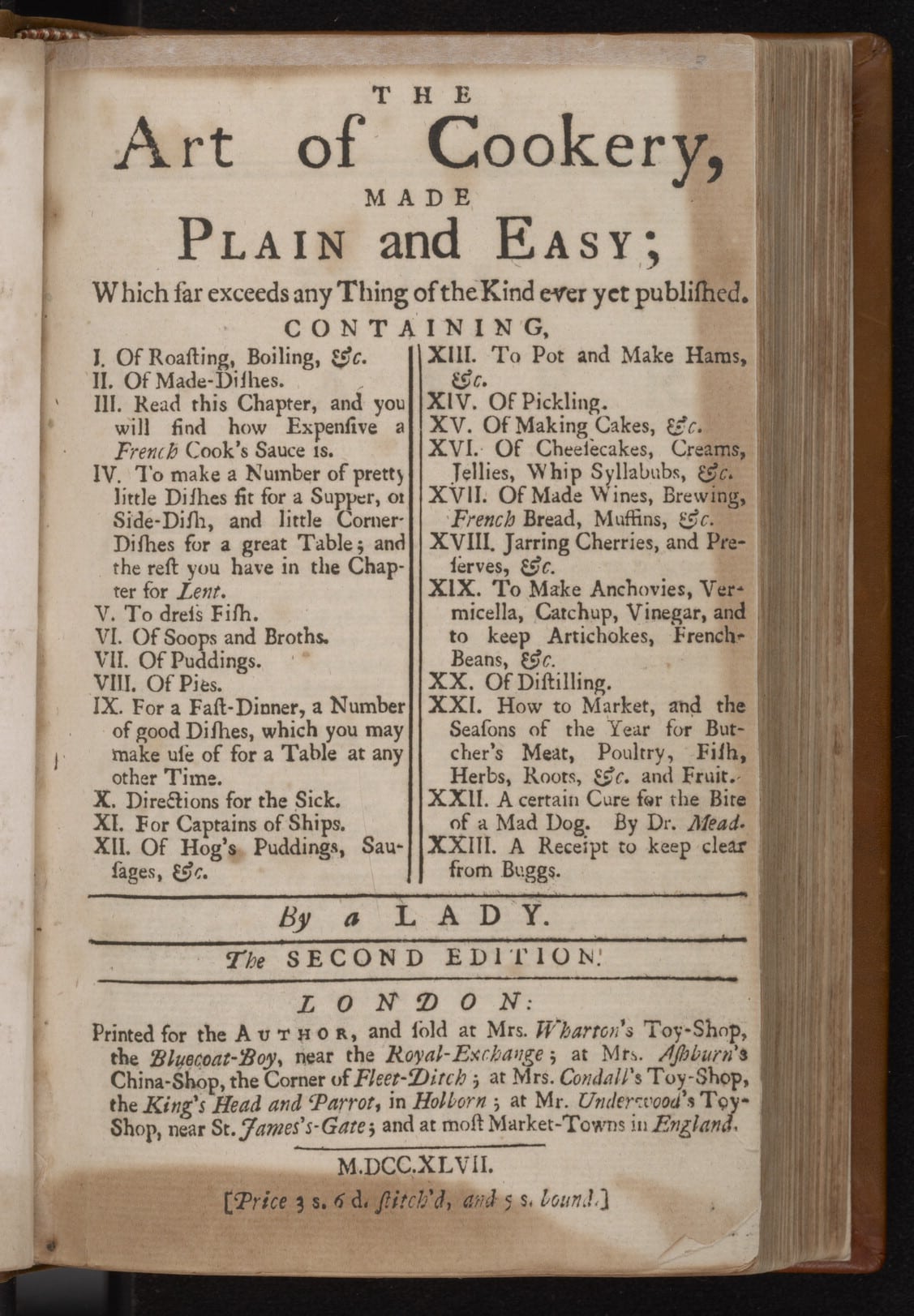

- 1805 – The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse

- 1847 – Plain Cookery for the Working Classes by Charles Elme Francatelli

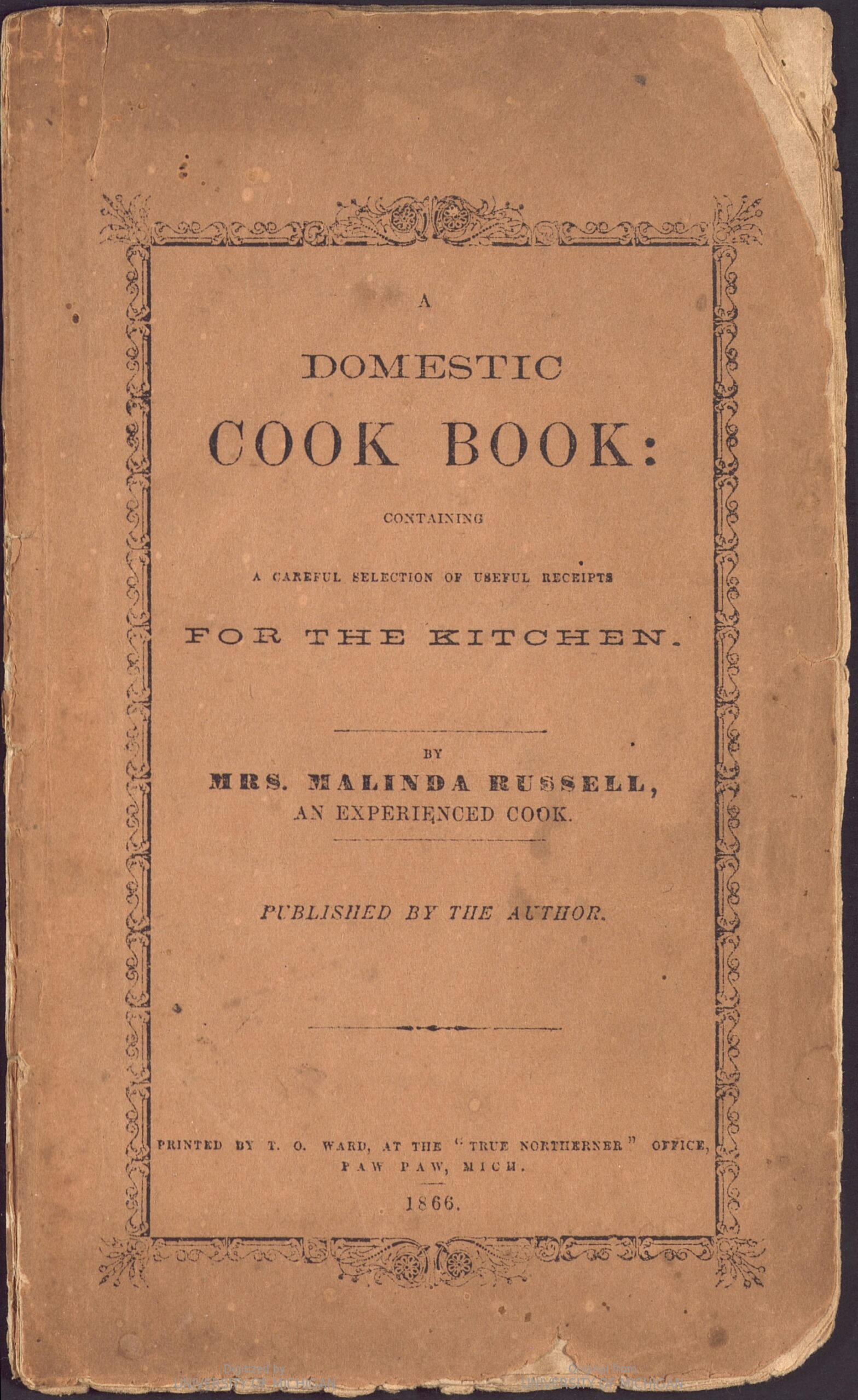

One of the first cookbooks authored by an African American, A Domestic Cookbook, was written by Malinda Russell, whose family were freed slaves. Most “traditional southern cooking” can be traced back to the recipes of enslaved and freed African American cooks, according to Dana Staves, in “A Brief (and Admittedly Incomplete) History of Cookbooks.”

- 1866 – A Domestic Cookbook by Mrs. Malinda Russell

1890 – 1940

Cookbooks published in the early 20th century began to be standardized, with recipes moving away from minimal instructions tucked in among the ingredients to the step-by-step format with a full ingredients list that modern cooks are familiar with.

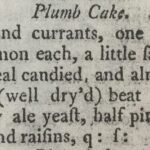

Early cookbooks presumed a certain level of culinary knowledge and were written with ingredients and instructions intermingled, like this recipe from American Cookery.

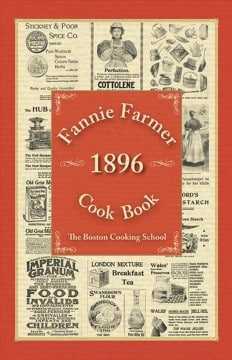

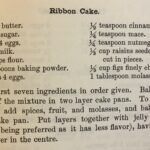

Near the beginning of the 20th century, as the publishing industry became more advanced, the recipe format was standardized, with separate ingredient lists and step-by-step cooking instructions, like this recipe from the Fannie Farmer 1896 Cook Book: The Boston Cooking School.

- 1896 – The Boston Cooking School Cookbook by Fannie Mae Farmer

- 1927 – The Farmer’s Guide Cook Book

- 1932 – Cookery for Today by Ann Batchelder

- 1936 – The Joy of Cooking by Irma S. Rombauer

- 1934 – Hershey’s 1934 Cookbook by Hershey Chocolate Company

1940 – 1970

In the mid-20th century, additional printing advances meant cookbooks could now include photographs to accompany recipes. Betty Crocker’s Picture Cookbook, published in 1950, was among the first to use photos, though the practice has become an art form all its own in contemporary cookbooks.

- 1950 – Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book

- 1996 – Betty Crocker’s New Cookbook

With the proliferation of television came the new “celebrity chef,” with hosts like Julia Child, who brought French cooking techniques to American households, and James Beard, whose show focused on traditional American cuisine. These television shows created an eager readership for their hosts’ cookbooks, like Child’s The Art of French Cooking, and Beard’s Cook it Outdoors.

- 1940 – Cook It Outdoors by James Beard

- 2012 – The essential James Beard cookbook : 450 recipes that shaped the tradition of American cooking by James Beard

- 1961 – Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle

1970 – Present

More recently, the term “celebrity chef” refers to celebrities–like actors, musicians, and politicians–who publish cookbooks that reveal as much about their lives as their food tastes. This is also the age of the food-blogger-turned-cookbook-author, whose stories about food, along with high-resolution photos, offer the reader a sensory experience before they ever enter the kitchen.

- 2009 – The Pioneer Woman Cooks by Ree Drummond

- 2016 – Cravings by Chrissy Teigen

- 2018 – Whiskey in a teacup by Reese Witherspoon

Food shows on cable television and streaming networks have taken the Julia-Child-style cooking show to a whole new level, turning a simple “kitchen show” into a highly produced docudrama and travelogue. Samin Nosrat’s Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat on Netflix is a perfect example. But even with the changing format, these shows still leave audiences hungry for more cookbooks.

- 2017 – Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking by Samin Nosrat

With even more accessible printing, families, organizations and communities also have the opportunity to create their own cookbooks. These “compiled cookbooks are critical sources of information about foodways, or the way a certain culture sees, prepares, and enjoys food,” writes Erin Blakemore in “What Amateur Cookbooks Reveal About History” on JStor Daily. “They contain hints of a group’s food habits, the kinds of foods eaten in the home, a kind of ‘autobiography’ of the food of the group that compiled the book.”

Cookbook Exchange

If you love cookbooks as much as we do, then don’t miss our Cookbook Exchange throughout the month of September. Anytime from September 1 through September 30, bring in one of your own cookbooks – used but still in good condition – and exchange it for a “new to you” one. Participants also are eligible to enter a drawing for a copy of the book I Dream of Dinner (So You Don’t Have To) by New York Times contributor Ali Slagle. Visit the Teen & Adult Reference Desk for more information.